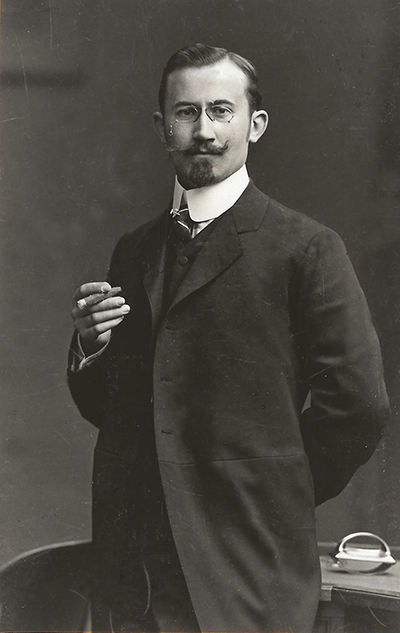

Christian Hülsmeyer (born in 1881 in Eydelstedt/Lower Saxony) was already enthusiastic about the laws of physics as a young man. He abruptly abandoned his teacher training and began a new apprenticeship at the Siemens-Schuckert factory in Bremen.

He was fascinated by the properties of electromagnetic waves: if they are directed against a metallic object, the wave is reflected back to the receiver. Hülsmeyer wanted to use this property to build a device that could send and receive electric waves. He hypothesized that such a device could be used to determine the position of ships and trains.

In 1902, he moved in with his brother Wilhelm, who had a textile business in Düsseldorf, where he wanted to continue working on his invention and eventually market it. He found a financial backer through a newspaper ad: Heinrich Mannheim, a Cologne leather merchant and investor, was convinced the invention would be a success. Together they founded the company Telemobiloskop-Gesellschaft Hülsmeyer und Mannheim. Heinrich Mannheim provided the start-up capital of 5,000 gold marks (the equivalent of around €26,000 today).

The Telemobiloscope

On April 30, 1904, Christian Hülsmeyer was granted a patent for his “method for reporting distant metallic objects to an observer by means of electric waves.” He named the associated device a “Telemobiloscope” (remote motion detector). In November of the same year, he added a distance measuring unit to the device. Now, nearby objects could not only be located, but the distance to the observer’s own location could also be determined.

The experiment

The high-frequency engineer demonstrated his invention to the public for the first time in May 1904. He set up his apparatus on what was then the Dombrücke bridge in Cologne and pointed the antennas at the ships’ path of travel. As soon as a ship appeared within a radius of 3km, the device generated a ringing sound – it was a sensation! A short time later, Hülsmeyer presented the Telemobiloscope to an expert audience in the Netherlands.

End of research

The press coverage reached as far as the USA, and journalists praised the invention. Nevertheless, no commercial user could be found. Hülsmeyer contacted companies in the shipbuilding industry, the new radio industry, and the navy – but although ship collisions were common, they all kindly rejected the Telemobiloscope. The reason they gave was that the steam whistles currently in use could be heard over a greater distance than the range of the Telemobiloscope. As all efforts remained fruitless, Hülsmeyer abandoned any further development of the device in 1905. Telemobiloskop-Gesellschaft Hülsmeyer und Mannheim was dissolved. The technology enthusiast had invested a total of around 25,000 gold marks (today around €130,000) in developing, patenting, and marketing his invention.

Eventually, he founded a company for boiler and apparatus construction and focused on anti-rust filters, water filters, and other parts necessary for hot water. He got married, had six children, and applied for more than 180 further patents in Germany and abroad, which made him a wealthy man.

Technology

Hülsmeyer based his invention on Heinrich Hertz’s discovery that electromagnetic waves are reflected by metallic objects. This also works at night or in poor visibility and is therefore suitable for maritime applications. If you can measure how long it takes for a wave transmitted to reach the receiver again, you can calculate the distance of the reflected object. In contrast to radio telegraphy, which had also just been discovered and worked with long waves, Hülsmeyer used short waves in the decimeter range. Hülsmeyer’s Telemobiloscope consisted of:

- a transmitter and a receiver arranged directly next to each other

- a spark coil to generate the high-frequency waves

- a coherer receiver (detector for electromagnetic waves)

Late fame

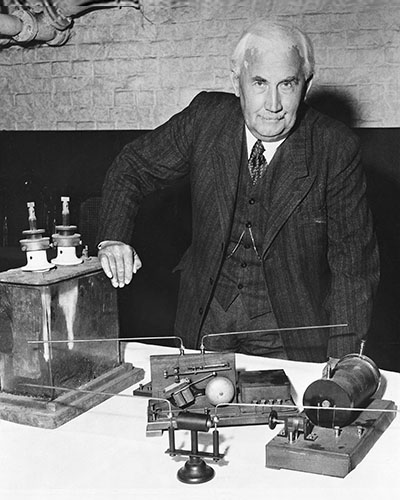

Meanwhile, in the 1930s, various scientists around the world were working to develop a radar system. The Second World War showed how necessary this invention was, especially for timely aircraft detection. At the beginning of the 1940s, Scotsman Robert Watson-Watt was knighted by King George VI for the invention of radar. A historian then remembered Christian Hülsmeyer and published an article about his research, which led to discussions reaching up to the highest levels of government. It was later agreed that Robert Watson-Watt was not the sole inventor of radar. In the 1950s, Hülsmeyer received late honors, from Konrad Adenauer among others. Christian Hülsmeyer died in 1957 and is buried today in Düsseldorf’s Nordfriedhof cemetery.

The world’s first radar is now housed in the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

Header: Deutsches Museum Munich)

![[Translate to English:] Zeichnung aus der Patentanmeldung 105546](/fileadmin/images/innovationen/01-meilensteine/Telemobiloskop/Telemobiloskop_-_Der_Vorl%C3%A4ufer_des_Radars_d.jpg)