Film is probably one of the most important media there is today. The invention of sound film, the patents associated with this, and the parties involved play a particularly important role in the development of film as we know it today.

As early as the mid-1880s, the films shown in the theatres were accompanied by vaudeville orchestras. Sound – music in particular – was therefore added to the images on screen for entertainment purposes from the very beginning. However, it was a good 30 years between the invention of the motion picture and the first successful screening with synchronous images and sound.

At the end of the 1920s, the American companies Warner Bros. and Western Electric developed the sound-on-disk system. This involved connecting the film projector to a record, which in turn was read by a stylus. This meant that the audience could see the images and, for the first time, hear the sound as well. The first feature film produced using this process was the Warner Bros. film “The Jazz Singer”, which premiered in New York on October 6, 1927. The audience was thrilled to hear the famous words “Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain’t heard nothing yet!” spoken by vaudeville star Al Jolson, which was the first time they had seen someone on screen and heard them speak at the same time. That was the breakthrough of the sound film.

At the beginning of the 1930s, the optical sound process replaced the sound-on-disk process. As a result, the sound film became more and more popular and spread all around the world.

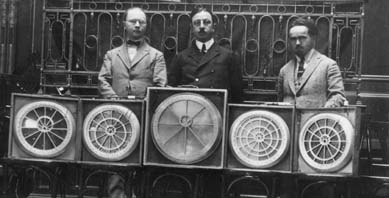

But the optical sound process was not first developed in the 1930s. As early as 1918, three German sound engineers, Joseph Engl, Joseph Masolle, and Hans Vogt, invented a method called Tri-Ergon, which linked a running film strip with a soundtrack traced by a beam of light. In 1923, they handed over the patent rights to their technology to Swiss company Tri-Ergon AG, before German film company UFA decided to take a stake in 1925. On December 20, 1925, the first short sound film entitled “Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern” was shown in Berlin’s Mozartsaal. However, the sound failed during the premiere and UFA withdrew from the sound film project.

It was only with the involvement of the Ton-Bild-Syndikat AG that the optical sound process became a success.

The Ton-Bild-Syndikat AG (Tobis) was founded on August 30, 1928 in Berlin with the merger of Tri-Ergon Musik AG, H. J. Küchenmeister Kommanditgesellschaft, Deutsche Tonfilm AG, and Messterton AG. This marked the union of various European sound film patent holders as well as their financiers. Their goal: to standardize sound film technology. By doing so they also wanted to rival the American sound film industry.

A German company on paper, Tobis was largely backed by Dutch and Swiss investors from the beginning.

Andre Struve and Dirk Out represented the Dutch interests. Together with inventor Heinrich Küchenmeister, Struve had founded the Küchenmeister Group, which became successful with its invention of the phonograph and the improvement in sound reproduction that accompanied this. Out, who was a partner in a bank in Amsterdam, had also invested in Struve, among other companies. Meanwhile, Küchenmeister was working on the Meisterton patent, an improvement on the Tri-Ergon technology. Meisterton technology, which used standardized 35mm film and could thus be installed in an existing sound box, premiered in November 1927 and led to the founding of Küchenmeister’s Internationale Maatschappij voor Sprekende Films NV, which was directly involved in the founding of Tobis.

In addition to Sprekende Films NV, which held 36% of the Tobis shares, Tri-Ergon had a 26% stake. The patents of the two shareholders complemented each other. Only through mutual use could the individual parts be produced and further developed.

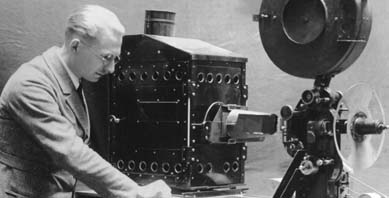

The Tobis system premiered on January 16, 1929, with the film “Ich küsse Ihre Hand, Madame” and a song interlude sung by Richard Tauber. It was then two months before Walther Ruttmann’s 40-minute film “Melodies of the World” appeared. At the end of September of the same year, the first full-length German sound film, “Das Land ohne Frauen” by Carmine Gallones, which was just under two hours long, was released in cinemas.

However, neither the film trade nor the electrical industry was represented in Tobis. This changed in March 1929 when Tobis signed an exclusive contract with two German electrical engineering companies, AEG and Siemens & Halske, who were able to produce large quantities of sound film equipment for the European film industry under the name Klangfilm. Both sides profited enormously from this partnership. Tobis now had access to industrial capacities and Klangfilm could use Tobis’ patents to refine and develop its products.

While Tobis grew into a market-leading company with a growing number of patents, American competitors started to become aware of the German film industry. A legal dispute over patent infringements arose, in which Werner Cohausz, one of the founders of the law firm Cohausz & Florack, played a central role. As head of the patent department of Klangfilm GmbH, he inspected a sound film apparatus in a Zurich cinema in 1929 and came across details of the sound film playback equipment of Western Electric and Radio Corporation of America. His findings allowed him to take targeted action against patent infringements by the competitors. Working with a Swiss lawyer, he also succeeded in a lawsuit against the first screening that used the apparatus.

But there were not only disputes between the German and American companies. Even within the American film industry, the individual companies were not in agreement. On April 10, 1930, Warner Bros. signed a contract with Sprekende Films NV, agreeing that Warner Bros. was to receive 50% of the future profits of Sprekende Films NV and Tobis in return for a payment of $1.75 million. As a result, Western Electric, which had previously refused to take part in any negotiations with its European and German opponents in the patent disputes, had no other option left. The company had to enter negotiations to secure its position in the American and international markets.

These negotiations are known as the Paris Sound Film Peace Treaty. This was signed on July 22, 1930, and saw representatives of the Tobis-Klangfilm Group and the US sound film industry agree to divide up the areas of interest. After this, only the technologies of German companies were allowed to be marketed in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and the Balkan states, while the American market was transferred to US companies. Free competition was agreed for all other countries. In addition, an agreement was reached that each could use the other’s patents and that sound films made using a party’s own recording equipment could be shown using the sound system of their competitor.

With the release of the patents, there was nothing left standing in the way of a complete switch from silent film to sound film. The proportion of sound films on the German market rose and rose. While in 1929 only 5% of all motion pictures were sound films, by 1931 this figure was already 39%.

However, this changeover also meant huge costs. Many cinemas could not afford to purchase the equipment necessary. Film industry profits fell by about 60%, and both the screenings of the films and their production could only be maintained through subsidies from Tobis. Tobis thus developed more and more into a film financing company. But it could not finance the entire film industry, and so by mid-1933 many companies in the film industry had ceased operations.

In addition, the rising anti-Semitic movement under Hitler led to several countries imposing a boycott against German films, resulting in a dramatic drop in proceeds from exports of German motion pictures. Tobis, a company that had once held a monopoly and been of such importance in the German film industry, making such a huge contribution to the development of sound film, was now restructured into a state-administered company.

The sound film, however, remained and prevailed in the market. And, above all, the Paris Sound Film Peace Treaty shows to this day how important patents are for the invention and further development of innovations.

(Header: David Mark - Pixabay; detail: DIF (German Film Institute), The Jazz Singer 1927 poster marked in the public domain on Wikimedia)